A Tale of Two Wildwoods

In the 1950s and 1960s, Wildwood was a mecca for the leading African American jazz, blues, and R&B singers of the day. Over 50 clubs and music halls dotted the streets and lined the boardwalk. It was the dawn of rock and roll, and these were the artists who were shaping it.

During those days Wildwood was a stop along what was informally called the “chitlin circuit,” the towns and neighborhoods where African American musicians, singers, and comedians were welcomed and could find lodging and restaurants in the era of both official and de facto segregation. In its heyday, Wildwood sported venues from intimate bars to large halls that could accommodate upwards of 1,000 people.

Although not officially segregated like southern towns, there were clearly two Wildwoods. On the west side of the railroad tracks, which ran along New Jersey Avenue, extending from Davis Avenue to Schellenger Avenue, was a significant African American neighborhood. In the summer, music echoed from the clubs along these streets—the Club Esquire, the Savoy, the Golden Dragon, and the High Steppers Club, among others.

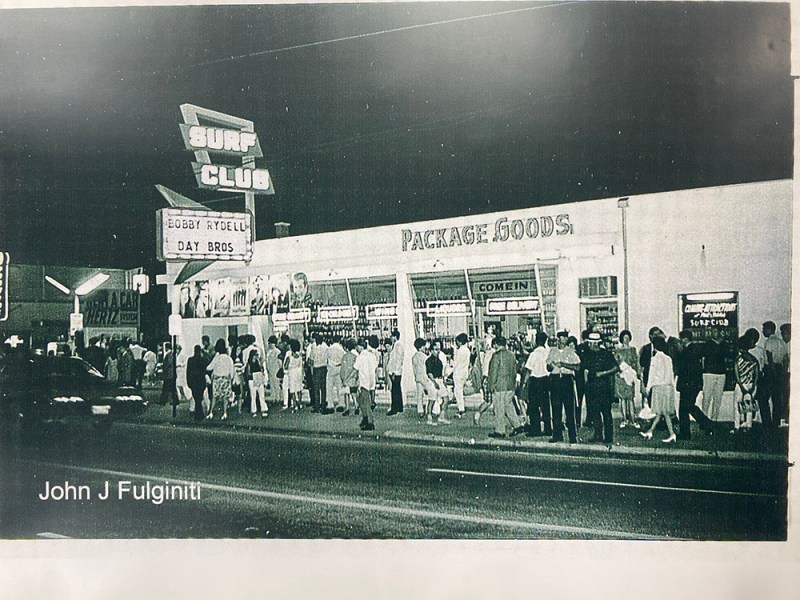

The predominantly white neighborhood was on the other side of town, across the tracks and extending to the ocean and along the boardwalk. It featured other places known for music, including the Rainbow Club, the Hofbrau, the Starlight Ballroom, and Phil and Eddie’s Surf Club. And along the streets were hundreds of motels, in mid-century modern style, with neon lights, space-age imagery, angular shapes, and fake palm trees.

The list of performers who played at all these venues includes such world-famous names as Count Basie, Ethel Waters, Dizzy Gillespie, Ella Fitzgerald, Dinah Washington, Sarah Vaughn, Lionel Hampton, Sammy Davis, Jr., Louis Armstrong, Little Richard, Chubby Checker, Johnny Mathis, The Drifters, Wilson Pickett, The Shirelles, The Platters, Steve Gibson and the Red Caps, Damita Jo, and The Treniers.

Atlantic City had music too, but it attracted an older crowd who came for more staid sounds. Younger beach-seeking tourists from Philadelphia and New Jersey, white and Black, preferred Wildwood. Wildwood also had a host of college kids working at the shore for the summer, coming from schools in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and the Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) in the South. They all were wild for the sounds emanating out of the local night spots.

People who lived full-time in Cape May County and nearby areas came, too. And if they could sneak away, so too did the high schoolers. Emily Dempsey, whose African American family has lived in Cape May for more than five generations, smiled when asked if she ever went to hear some of these great musicians play in Wildwood. She was still in high school, she told Cape May Magazine, when she heard that Dizzy Gillespie would be at one of the clubs. Although only a teen, she was determined to go see him. “I wasn’t old enough to go to a club, but my friend and I snuck in,” she reminisced. “When the waitress came to ask what we wanted to order to drink, I had no idea. I only knew to order water.” But she stayed for the show and got a photo from Gillespie’s staff, which he signed for her. She still has it today, some 70 years later.

While the musicians played to largely African American audiences in the westside clubs, on the other side of town the audiences were primarily white. And it’s there in 1960, at the Rainbow Club on the corner of Pacific and Spicer Avenues, that Chubby Checker reportedly first sang and danced the Twist.

“I’d like to maintain that story,” Ben Levy, whose parents owned the Rainbow Club from the 1950s to 1970s, told Cape May Magazine “A lot of people first remember hearing it there. The radio didn’t play a lot of things then. He was only 18, 19, and the story was my dad had to sneak him in and out because liquor was sold in the club. I remember holding the towel for him while he sang.” Levy was just a kid back then and he said Checker called him Benji. “He still calls me Benji. I saw him perform five or six years ago and he was yelling out, ‘Benji, Benji’ and my six-year-old granddaughter asked why he was calling me that.”

Levy remembers Wilson Pickett playing at the Rainbow, as well as the Drifters, the Platters, and Sammy Davis Jr. Count Basie did as well, although his jazz orchestra featured so many musicians that Levy’s dad needed to enlarge the stage for him.

But while these famous and soon-to-be famous musicians performed in clubs all over Wildwood, they could not stay in many of the hotels they performed in nor even close to where they were headliners. They were not welcome on the white side of town.

Gail Cohen grew up in Wildwood and is now secretary of Preserving the Wildwoods, a group dedicated to maintaining the island’s architecture and history. Her father, Murray Hayman, was a municipal judge in Wildwood Crest. Cohen remembers the family having dinner one night when her father got an important call. “It was from the people who were accompanying Sammy Davis, Jr. They had made a reservation for him at a motel in Wildwood Crest. When he got there the people wouldn’t let him in. My father made some calls and got him into another motel. We got tickets to his show as a thank you. I remember him at the show, telling what happened to him. And he said jokingly, ‘I’m sure it’s because I’m Jewish, not because I’m Black.’ And everyone laughed.”

While these musicians couldn’t stay in the motels and hotels on the white side of town, the African American community opened their doors to them and African American tourists. Many turned their large homes into rooming houses or rented out cottages, especially along Baker Street. Others established their own motels. The Green Book, a guide written for African American travelers during segregated times, listed for 1953 and 1954 alone 11 larger accommodations for Black patrons in Wildwood. And there were many other smaller places to rent a room.

The music scene also spurred other Black-owned businesses in the area. There were cleaners who laundered and pressed costumes and seamstresses who sewed them. Beauticians fixed the hair of the entertainers who ate in the nearby restaurants and diners.

William Cottman, Sr., speaks fondly of Carolyn’s Cottage, owned by his parents. “Ed Townsend, who sang ‘For Your Love I Would Do Anything’ stayed there,” he remembers. His mother always had a pot of stew or spaghetti sauce on the stove ready to feed a weary musician. Cottman, who was executive director of the Wildwood Housing Authority for 32 years, also recollects Steve Gibson and the Red Caps staying at the house next door. And across the street from Carolyn’s Cottage was the home favored by Count Basie.

“He would park his car in front of our house,” recalls Cottman. “He had a Cadillac convertible with [tailfins]. One night we went to his show. Then the next morning he was knocking on our door. I started to tell him how great his show was, but he interrupted and said, ‘I have a problem, there are two kids in my car.’ I knew right away they were mine. They loved riding in cars. But he said, ‘Mrs. Basie would love to take the kids for a ride.’ So, I figured how bad could it be to have Count Basie babysit my kids for a while.”

In 1955, Emma and Romuel Hawkins bought a summer home in Wildwood and built cottages and efficiencies on the property, calling it the Hermitage. Ella Louise and Frank Foster built the Elfra Court Motel in 1950 and their guests included such famous names as Dinah Washington, Fats Domino, The Supremes, Drifters, and Sammy Davis, Jr.

Sometimes these performers came to Cape May, to perform or to eat. Lois Smith, a singer and Cape May native, told interviewers with the Center for Community Arts about the time singer Mahalia Jackson let it be known that she was looking for some good seafood or fried fish. A Cape May local heard about it and told her he knew just where to go: Brown’s Cottage on Lafayette Street, which Smith’s mother owned. “And I had to set the table and all that kind of stuff. If I remember correctly, she liked clam stew or oysters. My mother made it with milk. And she came a couple of times.”

Late into the night, after the clubs had closed, many white musicians, even those playing in Cape May and Atlantic City, would come to Wildwood to jam with and learn the music the African American jazz and rhythm and blues artists played. “I knew this,” says Gail Cohen, “because I was friendly with two high school guys who snuck into these clubs, and I heard about it.”

Bill Haley and his band, a white country group dressed in cowboy outfits and called the Saddlemen, began playing in Wildwood in 1952, down the street from where the Treniers played—a high-energy African American song and dance group whose hits included “Rock the Joint” and “It Rocks! It Rolls! It Swings! It Jumps!”

Haley “would come in and watch us,” Claude Trenier told music writer Nick Tosches. And his band members would stop by the house where the Treniers were staying to talk. Milt Trenier writes on his website that, “The Treniers’ brand of swing-cum-R&B was undoubtedly an influence on Bill Haley, who saw them when both acts were playing summer shows in Wildwood, N.J.”

By 1955 Haley had changed the name of his band to Bill Haley and His Comets, had recorded, “We’re Gonna Rock Around the Clock,” and had the first rock and roll song to hit the top of Billboard’s pop singles chart.

By the 1970s the need for the “chitlin circuit” declined and Wildwood changed. The civil rights movement opened up all the clubs and hotels to Black performers. Black artists were able to record their music, and their songs were played on the radio. The need to tour to small towns and play at local clubs in order to publicize music had diminished. Selling records and large concerts became the key to making it in the business. Clubs in Wildwood closed. The businesses that supported them did, too. And as opportunities for jobs grew elsewhere, the African American community dwindled.

After the heyday of the 1950s and 1960s Wildwood went into a downturn. But even so at the turn into the 21st century there were still 300 Doo Wop motels in existence, and city preservationists and political leaders saw their restoration and promotion as a way for revitalization of the city. An effort was started to have the whole island placed on the National Register as a Historic District.

But it didn’t happen. The real estate boom of the early 2000s brought developers to town, and they in turn tore down many motels and built large vinyl-sided condos and hotels that clashed with the remaining 60s-style motels. Over 100 motels were destroyed in the five years between 2001 and 2006.

Today, on the west side of town many of the cottages are gone. While some of the buildings where the great musicians of the 1950s and 1960s once played still stand, none are music venues. On the east side of town, several of the more famous clubs have been repurposed. The Rainbow Club, where Chubby Checker once debuted his famous dance song, is now the Cattle ‘n Clover steakhouse. And Phil and Eddie’s Surf Club is now Schellenger’s Restaurant. Most of the others have been torn down.

Still there are buildings standing, and concerned local citizens have created an organization, Preserving the Wildwoods, whose goal is “to shine a light on the architectural, historical and cultural heritage of the Wildwoods and work toward preserving that heritage,” says Pary Tell, the group’s president.

She says that at a time when the number of Wildwood’s visitors is declining, keeping alive “the most identifiable culture associated with the city” is key to its revitalization. “The popularity of that time period is evident with the crowds that fill the city on 50s and 60s weekends, for antique car shows and for period musical entertainment events.”

The group has held a town meeting to educate people on the importance of preservation and their role in it and convinced two motel owners to preserve their Doo Wop architecture while upgrading their facility.

But they have an uphill fight. They are bucking a now hostile political leadership while at the same time a hot real estate market is spurring people to sell to developers. And in the Wildwoods, there are no Historic Preservation Commissions to enforce any preservation policy.

As in all things, only time will tell.