All Aboard! A trip back in time on the Fishing Train

Few people today have heard about Fishing Trains, which carried anglers to places for good fishing across the country. Railroads were a primary form of travel into the 20th century until many Americans owned cars. As train travel began dropping off, companies looked for ways of creating new opportunities for passenger travel. In Cape May and on the Jersey shore, railroads mimicked their steamboat predecessors and created excursions and special trips to generate passenger travel and compensate for decreased travel frequency. The result was the Fishing Train—special fishing excursions that became very popular not just on the east coast and in Cape May, but as excursions from many large cities to oceans, rivers, and lakes – to any place for good recreational fishing. The idea caught on. Railroads also operated one-day excursion trains for other activities at other times during the year and in other locations. Ski Trains carried people to winter resorts, while Hiking or Biking Trains went to Spring or Fall destinations.

Party Boat-goers all dressed up and ready to go, August 16, 1925. Image courtesy of the Lobster House

Fishing Trains delivered customers to Cape May for recreational fishing, a popular pursuit back to the 1800s when tourists hired town whale boat captains to take them on fishing excursions. They became a popular activity after World War I. Railroads connected city-living Philadelphia or Camden fishermen to various seashore resorts along the Jersey shore. Fishing Trains brought city people primarily from Philadelphia to Schellenger’s Landing, where the Lobster House is located today, using tracks installed initially during World War I to connect then-nearby military bases to rail lines. The Harbor Spur ran east from the Reading Railroad-Seashore Line just south of where the Cape May Canal is today, connecting the main tracks to Schellenger’s Landing. The Wissahickon Barracks, on the northeast end of Schellenger’s Landing, and the Wissahickon Naval Training Station at Sewell’s Point easily accessed the Harbor Spur. (The Wissahickon Barracks were dismantled in 1919, and the present-day Coast Guard Training Center and Base are located where the Naval Training Station was once located at Sewell’s Point.) The Harbor Spur was used until World War II to transport fish for shipment to Philadelphia and New York City markets. Trains were brought directly to Schellenger’s Landing, the fish unloaded from commercial boat holds into barrels, iced, and then loaded onto refrigerated freight cars.

Fishing Trains gained popularity around the 1920s and, along with commercial freight trains, used the Harbor Spur up until World War II when restrictions limited ridership and deep-sea recreational fishing opportunities. By 1950, both freight and fishing trains were permanently discontinued. Tracks were dismantled and the Harbor Spur disappeared.

Atlantic City was a primary destination even before 1920, as the trip from Philadelphia could take about 75 minutes. After 1920, changes in locomotives and tracks allowed trains from Philadelphia to make the trip to Cape May in under two hours, enabling Fishing Trains to be regularly scheduled, often daily, during the summer season. Sundays were popular excursion daysduring the May, September, and October shoulder months. The June 11th, 1922, The Philadelphia Inquirer reported that the “special fishing train leaving the Market Street ferries on Sundays will make the run in 90 minutes, without a stop.” A September 1926 Inquirer story noted that even though the summer resort season was over in Cape May, the anglers continued to fill the Sunday trains to capacity, projecting continued sport through October, when the trains would be discontinued until the spring. Fishing Trains may have been part of early attempts to create a shoulder season outside of the traditional summer season.

After the 1933 railroad merger into the Pennsylvania-Reading Seashore Lines, large ads about the Fishing Trains were run throughout the summer season in Philadelphia papers. Barnacle Bill, a character used in Pennsylvania Reading Seashore line ads, regularly advertised that “the catches are running high at the shore,” noting the daily and Sunday Fisherman Express direct to Schellenger’s Landing for $1.25 round trip. Trains left the Philadelphia Market Street ferry at 7:00 a.m., leaving Schellenger’s for the return trip at 4:40pm or when the fishing boats arrived back at the Landing.

Fishermen could fish from ocean or harbor piers, the beach, or deep-sea excursion boats called Party Boats. These boats had nothing to do with a party as some boats do today. Fishing Trains and Party Boats were interdependent. The Fishing Trains were a one-day excursion, so train and boat schedules were synchronized to allow the anglers to have as much time as possible at the fishing grounds. Trains carried the anglers and all their fishing gear, and whatever fish had been caught on return trips. One can imagine the anglers probably enjoyed a lot of conversation about fishing rods and gear, the best Party Boat captains, the types of fish to be caught, and on the way home, maybe a little competition about who caught the most or the biggest fish.

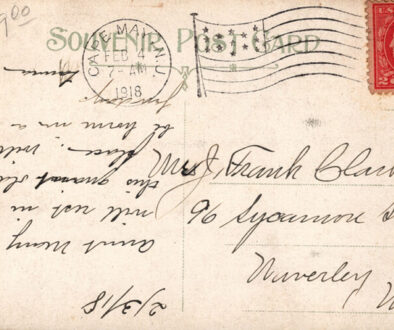

Postcards used to advertise the Party Boat excursions, with their corresponding vessels. Postcards courtesy of Dick Gibbs

The Party Boats were a serious enterprise catering primarily to men who were equally serious about fishing and what they might catch. Throughout the 1930s and up until the beginning of World War II, The Philadelphia Inquirer regularly described the popularity of the sport. One article noted: “Fishing Trains are daily, bringing hundreds of anglers to Schellenger’s Landing where the fishing boats under command of competent captains are leaving each morning for deep sea fishing trips.” The number of fish caught by anglers on a particular boat, with a particular captain, was often reported. On a good day, fishermen took home as many as 50 fish each, the varieties depending on where the boats went to fish and the time of year. In a 1933 article, the paper noted: “Fishing still lures hundreds of the followers of ‘Izaak Walton,’ large catches being reported from deep sea boats, piers, and harbor.” Walton authored a popular English guide, The Compleat Angler, setting a standard for men who would take up fishing as a serious hobby. This seminal work for anglers became the basis in the United States for the Izaak Walton League of America, which today has more than 200 chapters across the country. Fishing remains an activity of these clubs, many of which have broadened their missions to include activities emphasizing the protection and enjoyment of outdoor America.

Many Party Boat captains belonged to the Cape May-Wildwood Party Boat Men’s Association, a group formed to help support the captains and their work. For example, in 1936, the president, Robert Pierpoint, reported on this successful negotiation with the Seashore Lines to begin the Fishing Trains earlier than planned so that business could start on May 1st of that year. The Association’s members had also succeeded in creating the Sanctuary, a deep-sea fish preserve nine miles off the harbor inlet. The Sanctuary, still in existence today, was the first artificially created saltwater fishing bank in the world. The fishing captains, many of whom helped to construct the Sanctuary, attributed the high numbers of fish caught to the preserve. Many Party Boat captains took their boats directly to the Sanctuary so their customers would have plenty of fish to take home.

Both Fishing Trains and fishing were impacted by the Second World War when gas was rationed, Party Boat skippers were fighting in the War, and many boating restrictions were in place in Cape May waters to protect the country from German submarines and other potential attacks. Recreational deep-sea fishing was banned in 1942 and not reinstated until 1944, as restrictions were lifted, and gas became available. President Pierpoint of the Party Boat Association noted that 1944 would be a particularly good year for fishermen since there had been virtually no saltwater fishing since the 1942 ban. Operational Party Boats more than doubled from fewer than 25 in 1944 to 56 in 1946. Party Boats increased the average fare by 50 cents to $3.50 to adjust for the rising cost of bait. Anglers and Party Boat captains were looking forward to a return to pre-War business. In the spring, the Inquirer reported that “commercial fishermen were reporting better than average catches …claiming the fish may be ahead of schedule” and noted, “Just about the only thing that is sure is that there will be plenty of fishermen. Fish or no fish.”

By 1947, Cape May had 58 Party Boats in service. Another 44 were based in Wildwood at Otten’s Harbor. Another Inquirer article noted that express buses would begin operation from Philadelphia to Schellenger’s Landing in mid-May 1947, reporting “negotiations are underway for Camden to Cape May special trains, a pre-war service the railroads are reportedly loath to resume.”

The Fishing Trains eventually became a thing of the past and were not resumed after the War with daily pre-War summer schedules. Some periodic special excursion trains were run until the early 1950s when the Harbor Spur was removed. Perhaps after the War, the Seashore Line already had plans to permanently discontinue the Harbor Spur, or maybe enough people would get to the shore for fishing in their own cars or might choose to make deep sea fishing a part of their summer vacation rather than a one-day excursion.

Fishing has always been an integral part of Cape May and its community. Deep sea fishing continues in popularity today, but perhaps not with the degree of intensity of those anglers who rode the pre-war Fishing Trains. Commercial fishing remains a primary Cape May County industry, as it has been since the early 1800s, but today is second to tourism. Schellenger’s Landing and Wildwood/Lower Township ports around the Harbor are still the largest ports in Cape May County and one of the largest commercial fishing ports on the east coast.

We may no longer have those Fishing Trains that became obsolete in a short number of years, but as long as we have people who love to live near or visit the sea, we will always have boats and we will always have fishing.

Letter from a reader

I just read the article (Spring 2023) about the Cape May fishing excursion train from Philadelphia.

I grew up on Lafayette St (then moved to Washington St) at the foot of the “little bridge.” I remember the steam train backing past the Anchorage Inn, across Rt. 9, to Schellenger’s Landing (now Lobster House).

I could very well be the boy in the last photo standing next to the steam engine. The trains were fascinating to me with all the hissing and clunking noises. I would run across the little bridge to watch the trains come in the morning and leave in the afternoon. As I recall, the engines did not sit there all day, they uncoupled and left the cars. Some of the trains were so long that they stopped blocking Rt 9 until all the fishermen got on or off. There was almost no car traffic then.

I knew many of the boats (Capt Johnson, Bucky, Vaud J, etc) and their captains. My great-grandfather and father ran the Isaac Walton. My great-grandfather built the Isaac Walton in Carpenters Boatyard during Prohibition and I am certain he was a rum-runner.

Thank you for the article, it sparked many memories of time past.

MICHAEL GRIMES

Hampstead, NC

PS: I departed CM in June 1971 after graduating from CM schools, commercial fishing, serving in the Navy, then college, and on to another life as a BNDD/DEA Special Agent.