All-American Recovery: The Bald Eagle

On an ordinary afternoon in March, Cape May resident Linda Portewig was standing outside with her son when she witnessed a fierce battle suddenly erupt in the sky. To her great surprise, two Bald Eagles had forcefully collided and appeared to be stuck in a deadly embrace as they spiraled down through the air. Linda and her son watched in awe, fully expecting the eagles to break off before smashing down to earth. But these eagles were locked in a death grip, their powerful and deadly talons unbreakably intertwined. As the birds neared the treetops they quickly maneuvered to avoid any large branches and landed in some rose bushes with an audible crash.

Forty years ago, two Bald Eagles appearing over a Cape May backyard would be an almost unimaginable sight. Their precipitous decline, followed by a miraculous recovery, is a rare conservation success story. At their low point in the early 1970s, the American Bald Eagle was on the edge of extinction, especially in the lower forty-eight states. Like many species in the 19th and 20th centuries, and despite its national reverence, the Bald Eagle had been mercilessly persecuted by humans on multiple fronts. In the entire state of New Jersey there was just one breeding pair, but their attempts were unsuccessful.

Bald Eagles were nearly eliminated from Eastern North America. A number of factors contributed to their decline, including indiscriminate shooting, habitat loss, and overfishing; but the main culprit was identified as the pesticide DDT, a chemical first used during World War II. This poison was especially toxic to insects, and was used after the war as an agricultural insecticide and as an agent to destroy mosquito populations in communities around the United States. The toxicity to humans and wildlife was unknown at the time, nor was its effect on the environment. Apex (or top of the food chain) predators—including large birds like the Peregrine Falcon, Bald Eagle, Brown Pelican, and Osprey—were particularly hard hit by chemical spraying. As it worked its way up the food chain from insects to fish, and smaller animals in greater quantities, predators accumulated large amounts of the pesticide in their tissue; many were outright poisoned. However, the most insidious problem developed within their reproductive systems. The mechanism is still not completely understood, but it is known that DDT affects calcium absorption during an important period of eggshell development. Despite an egg’s natural strength, DDT exposure causes drastic thinning of the shell. Once the mother laid her eggs, the simple weight of her brooding would break the eggs underneath her. Unable to reproduce, the populations of many raptors and other predatory species quickly fell.

In Rachel Carson’s seminal work, Silent Spring (1962), she highlights the many detrimental effects of DDT on wildlife and humans. Her book is credited with jumpstarting the burgeoning environmental movement in the 1960s and 1970s, resulting in a major change in how Americans viewed and used our natural resources. Legislation such as the Clean Air Act, Water Pollution Control, and—most important for the Bald Eagle—the Endangered Species Act, set mandatory protections for vulnerable species in the United States.

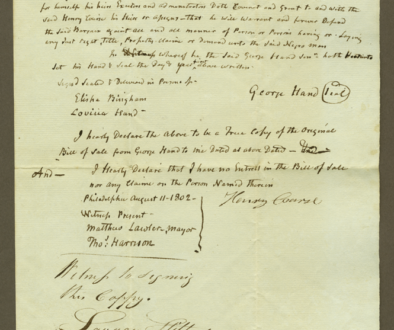

To gain some perspective on Bald Eagle recovery in New Jersey, I spoke with Wildlife Biologist Larissa Smith, who works on the Bald Eagle program for Conserve Wildlife New Jersey. I first asked about initial recovery efforts. “New Jersey and the rest of the east coast had a couple of major challenges,” Smith answered. The first challenge, the elimination of the use of the pesticide DDT, began with its ban in 1972. Although it can persist in the environment, the ban on new spraying in the early 1970s would limit new exposure to wildlife. The second major problem was the virtual elimination of the breeding population of Bald Eagles in the state. With just one pair remaining, it was unlikely the Bald Eagle population would rebound without help.

“In 1983,” Mrs. Smith said, “the State Endangered Species program began a ‘hacking’ program, eventually releasing 60 Bald Eagles over an eight-year period.” Hacking is a technique used to increase an egg or chick’s chance of survival. New Jersey’s only Bald Eagle pair—the Bear Swamp pair in Cumberland County—had been unable to successfully hatch an egg in many years because of eggshell thinning. State biologists removed their eggs from the nest after they were laid and incubated them until hatching, then reintroduced the chicks to the parents. “With intensive efforts by biologists within the Endangered Species program, by the mid-1990s Bald Eagles were able to reproduce on their own,” Mrs. Smith said. New Jersey Fish and Wildlife and organizations like Conserve Wildlife continue their work today with the help of many volunteers to protect and monitor nesting Bald Eagles in New Jersey.

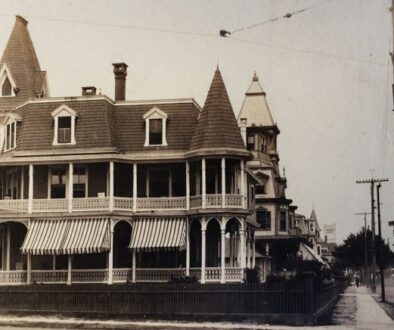

Cape Island currently has a territorial pair of eagles that has successfully fledged young birds for several years through 2015. With the population of Bald Eagles soaring in New Jersey, it is no wonder clashes between individual birds are becoming more common. Perhaps this is part of the reason I ended up in Linda Portewig’s backyard after receiving a call about the two Bald Eagles stuck in a rosebush. A bit incredulous of the call at first, I knew that Linda’s identification of the birds as Bald Eagles was pretty straightforward. It didn’t take long to decide who to call. I contacted eagle researchers Mike and Trish Lanzone, conveniently located down the street in West Cape May, with the news that there were two grounded eagles. They certainly didn’t waste a minute; 30 seconds into the phone call I heard a car door opening and Mike yelling for Trish to come out to the car. Mike and Trish took off running (in jeans and t-shirts mind you—no protective outerwear) directly into the overgrown rose bushes for the tangled eagles. After one bird was freed from the tangles and expertly wrangled by Trish, Mike grabbed the second bird by the legs as it attempted to fly away. By the time I arrived on the property there were two comfortably bundled eagles lying on the ground, ready to be processed.

The first thing you notice about a Bald Eagle, even one bundled and masked comfortably on the ground, is their size. These birds were particularly large females, and in the raptor world, the girls rule. It’s not yet clear why raptors show such extreme reverse sexual dimorphism. In fact, the females can be up to one third larger than their male partners. It may have to do with egg production, territorial defense or having slightly different niches in their choice of relative food size. Regardless, Bald Eagles are one of the largest birds of prey in North America, having a wingspan of up to seven and a half feet! Their huge size makes them expert soaring birds.

Sticking out from underneath their feathers were yellow legs and feet with the sharp, nearly finger sized talons bagged up for safety. This is by far the most dangerous part of the bird to a human handler, as they are more than capable of piercing flesh. The raptor talons are designed to quickly subdue and kill prey. Bald Eagles are typically thought of as fish eaters, but they commonly hunt ducks and sometimes small mammals like rabbits and muskrats. They also commonly feed on carrion. A hungry eagle has no qualms about pushing out vultures over fresh road kill. Ducks are a common tell that there is a bald eagle nearby. If you notice a flock of ducks suddenly careen off a pond into the air, it’s a good time to look up, because more often than not they are reacting to a flyover Bald Eagle.

Another Bald Eagle foraging characteristic is simply to steal from other birds. Often one of the best places to view this piratic behavior is from the Hawk Watch platform at Cape May Point State Park during fall migration. Migrating Osprey are commonly spotted flying high over the bunker pond with their freshly caught meal, seemingly showing off their skills as fishermen. I often wonder why they do this, since it sometimes attracts the attention of a hungry eagle who beelines straight for the Osprey. Just as the first observer yells, “Eagle coming in hot!” the Osprey realizes his predicament and quickly ascends higher into the air away from the pursuing eagle. Unfortunately for this Osprey, Bald Eagles are persistent bullies, and being weighed down by a two-pound Menhaden doesn’t help. Eagles are powerful flyers and capable of rapid ascension when need be. As the eagle nears the Osprey, the desperate fish hawk will attempt to weave away but it’s often in vain. There’s an audible gasp as the eagle closes in, extending his talons out to attack, and then the Osprey drops the fish from hundreds of feet in the air. The Eagle anticipates this victory and as soon as the fish drops it agilely tucks in its wings, engaging in a steep dive toward the prize. One hundred feet before the fish hits the ground, the eagle reaches terminal velocity and adeptly snatches the flying fish right out of the air.

Even after witnessing this impressive show, observers usually side with the Osprey, not impressed with the outright thievery of our National Symbol. Perhaps this is why Benjamin Franklin apparently argued against the Bald Eagle’s form on the presidential seal. Franklin was familiar with the natural world and certainly knew of the Bald Eagles’ unsavory exploits!

Meanwhile in the Cape May back yard, both eagles were inspected for broken bones and fortunately had not sustained any serious injuries—a bloody eyebrow on one of them seemed to be the extent of the damage. Their wings were stretched out and measured, beak measurements taken, and they were weighed upside down from a portable scale. The two eagles were also bled to gather DNA for sex determination, to test for heavy metals in their blood, and assess their overall health. Finally, each bird was given their “bling,” a metal band on the leg of the bird meant to identify them if they are recaptured in the future. These bands are entered into a national database at the Bird Banding Lab, run by the USGS (United States Geological Survey). Neither of these birds had been banded before, but if they are recaptured they will be identified. Mike and Trish posited that one of the two eagles was probably from a local nesting pair.

Bald Eagles lay their eggs very early in the season compared to most other birds. In New Jersey, pairs lay their eggs between the third week of February and the first week of March, with an average clutch size of two to three eaglets. Eggs may hatch late March through early April, and the nestlings are entirely dependent on their parents for food in the nest for two to three months. After they fledge (leave the nest) young eagles continue to rely on their parents throughout the summer until they learn how to hunt and forage on their own. According to Conserve Wildlife biologist Larissa Smith “the population is doing really well and has shown a particularly strong increase in the past 10 years.” Last year, biologists and volunteers documented 216 young in 132 nests throughout the state. In Cape May County, Bald Eagles fledged about 12 young last year, mostly in the northern part of the county. However, there are active nests along the lower bay shore, in Middle Township, and a resident Higbee pair.

The most exciting and rewarding part of rescuing a wild bird is the release. The first eagle was released by Linda’s son; it flew powerfully into the sunset. I was allowed to release the second bird after it was treated for minor injuries to its feet and head. After launching into the air it seemed to have no trouble until it lost some steam; my excitement turned to distress as it neared the tree line. Before it could clear the trees, it caught itself on some vines, and it seemed another rescue might be in order. Fortunately, it only took a minute before she regained her composure, untangled her feet and flew to a height above the neighborhood trees. The next day Trish Lanzone spotted the bird I had released perched on a telephone pole near the West Cape May Bridge, informing us that the rescue and treatment were successful and she was back to her normal routine.

Spotting a Bald Eagle majestically soaring free in the wild instills a sense of pride, and inspires those of us who are lucky enough to see this fascinating bird right here in our midst.