Beacon of Hope: Saving East Point Light

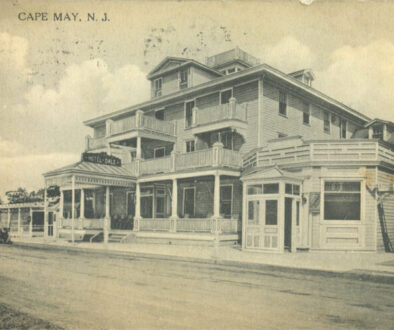

Nancy Patterson—artist and author—has been falling in love with lighthouses since she was a child. Her earliest memories involve visiting the Cape May Lighthouse, and dreaming about one day climbing to the top.

When her granddaughter was three, Nancy retraced her childhood steps. She took little Ella to see the lighthouses at Cape May and at Anglesea in North Wildwood, home of Hereford Inlet Lighthouse.

“Ella was infatuated,” says Nancy. “She kept asking questions. She wanted to go back and see more. She wanted to climb to the top. She wanted to know ‘How many steps? What is a beacon? Were there pirates? Can I live in a lighthouse?’ It was then I realized how important lighthouse stories are to children—to explain their maritime function, history and preservation. I am a preschool teacher, a watercolor artist, and a story teller. Laid up with the flu at the time, I said, ‘Bring me my pencils and sketch pad!’ I got comfortable in the covers, and with my supplies on my lap, I started to draw and write a child’s book on Cape May Light.”

The result is a 2012 watercolor illustrated book written in verse, May the Magnificent Lighthouse. As Ella ponders the lighthouse, she meets Mac the Mouse, who leads her up the 199 steps to the top and tells her about lighthouse duties and history.

A year later, Nancy published a second book, Hereford the Handsome Lighthouse. In this story, Hurricane the Squirrel helps Ella learn about Hereford Inlet Lighthouse, the 1874 Stick Style Gothic structure at Anglesea, and the only lighthouse of this design on the East Coast.

Nancy is currently working on a third book, East Point the Red Roof Lighthouse. This lighthouse is located near Heislerville, on the east bank of Delaware Bay, some 32 miles north of Cape May. She has not had time to finish this book, and has instead been preoccupied as the guardian angel of East Point Light, saving it from deterioration and Mother Nature’s wrath. First she led a successful restoration. More recently, more hands joined to protect the lighthouse from washing out to sea.

This past March, a record four nor’easters in three weeks swelled the bay and eroded the coastline. In the first nor’easter, storm-tossed bay waters breached the dunes, poured into the basement, lapped at the front step, and left the structure vulnerable to future storms. It was a time of crisis, and Nancy, as president of the Mauricetown River Historical Society, which oversees the lighthouse, went into survival mode with a team of state, county, and local officials and volunteers. It was the most calamitous time since she has been involved with the historic landmark.

It was 20 years ago that Nancy discovered the remote beacon quite by accident. As a youngster she spent every summer in Sea Isle City, where she was a champion sailboat racer. In later years, by then married with a family, she wanted to live by the water, preferably in a historic seafarer’s house. “My husband [Carl Tidy] and I were out looking for the perfect place,” she told Cape May Magazine. “We were meandering off old Route 47 in Cumberland County, and went down a road looking like a dead end. Suddenly, a lighthouse rose like a phoenix from the marsh. What a surprise! I jumped from the car—ran all around it. Lighthouses are my passion. I had been collecting New Jersey lighthouse photos, histories, legends, and watercolors, but I had never met East Point Light. It was love at first sight.”

Built in 1849, the lighthouse sits on a rise where the bay merges with the twisting Maurice River. It is the second oldest of New Jersey’s 11 lighthouses. Only the Sandy Hook Lighthouse, built in 1764, is older.

Nancy’s first instinct was to paint East Point Light. “It rests in tall grasses, on a wind-swept sandy point; its brick weathered, the roof, a faded red, the lantern room, elevated 40 feet above the Cape Cod Style keeper’s house. It’s a beautiful composition, and it’s very fortunate it has survived.”

Vandals set fire to the second floor in 1971. The blaze destroyed the lantern room and roof and seriously damaged the interior. Ironically, just weeks before the arson, a group of local citizens had organized the Maurice River Historical Society. Their goal was to restore the structure, which has strong emotional ties to the community. It serves as a testament to the area’s history of seafaring, oyster harvesting, and boat building.

The tragedy of the fire inspired the Historical Society to work even harder. They sponsored bake sales, garage sales, spaghetti dinners, and they applied for grants. The red roof was rebuilt and the green shutters were replaced. The lantern was reactivated in 1980. It had been discontinued by the Coast Guard in World War II during blackouts. The fear was that the light would direct German submarines upwards into Delaware Bay, threatening shipping channels to Philadelphia and the marine commerce along the bay.

Mauricetown is seven miles up-river from the lighthouse and the old oyster harvesting towns of Shellpile, Bivalve, and Port Norris. Settled by the Swedes in 1730, Mauricetown (pronounced Morristown) claims to have been home to more than 90 sea captains between 1846 and 1915. Remnants of the town’s zenith in the mid-19th century are evident today in lovely old houses in Victorian, Georgian, and Saltbox styles—most of which have been restored—and which are home to 150 residents.

It is in Mauricetown that Nancy and Carl eventually found a sea captain’s house of their dreams. “It was in dreadful condition,” says Nancy. “It took several years of intensive renovations to transform it into our comfortable Bayberry Cottage and Art Studio. It had been the home of Captain Daniel Bowen, who was lost at sea, as were two of his brothers. It is from the same era as East Point Light, which has always been an extension and a concern of our life here on the river and bay.”

In 2015 Nancy was elected president of the Maurice River Historical Society, there was a new board in place, and the group dove deep into the project of East Point Light’s full restoration. Historic preservation architect Michael Calafati of Cape May discovered that the familiar faded brick facade was not historically accurate, but had weathered over the years. His further research into its original appearance is now reflected in the restored exterior of the building, which is a bright white, produced by a coating of limestone whitewash, accented with dark green shutters, and a rich red roof topped by the shiny black lantern room flashing its red beacon.

Money for the restoration came from an $850,000 grant which had been languishing for more than a decade due to bureaucratic complications. Cumberland County agencies and the U.S. Department of Transportation worked with the New Jersey Historic Trust Fund to release the money, giving the Historical Society the ability to begin the restoration in 2016. The Historical Society manages the lighthouse in a lease agreement with the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. The lighthouse and its site are part of the 6,000-acre Heislerville Wildlife Management Area, which is overseen by the DEP’s Division of Fish and Wildlife.

The restoration was completed in a year. The rededication, which took place on September 10, 2017, was 168 years to the day that the first light shone on the bay. Old documents show that the U.S. Government paid $250 for the marshy half acre for the building site. Contractors Nathan and Samuel Middleton, who had just completed a second Cape May Lighthouse, received the construction contract for $1,975. The necessity for the light is documented in an 1894 Lighthouse Board report, which showed there were 500 vessels engaged in the bay oyster trade, employing more than 1,500 men.

East Point Light now functions as a museum. Its five rooms are furnished with simple essentials the lighthouse keeper and his family would have used at the turn of the century. The master bedroom furniture was donated by Doris Moore, a descendant of one of the ten keepers of the light. The entire site was placed on the National Historic Registry in 2015 after excavations revealed Native American and prehistoric artifacts.

There has been serious concern for years about sea erosion undermining the building. That worry was acutely manifested this March, which roared in like a lion on the winds of a bomb cyclone. Winter storm Riley raged from March 1–3. And, a parade of nor’easters soon followed; they were Quinn, from March 6–8, Skylar, from March 12–14, and Toby, from March 20–22.

During Storm Riley, the protective dune held for the first two days, but on the third day, lighthouse alarms sounded alerts; water was pouring into the basement, overwhelming the pumps. Waves breached the dune, cutting a hole, allowing water to rush in and surround the lighthouse. Nancy was receiving calls from the alarm company, but flooding of the marshland access roads prevented her, volunteers, and government agencies from arriving at the site until three days later. They then faced the grim reality that the lighthouse was “totally exposed,” says Nancy. There were television and newspaper reports of the just-restored lighthouse’s new vulnerability.

Maurice River Township crews plowed a protective sand dune bracing for Winter Storm Quinn on March 6, and Nancy wrote on the East Point Lighthouse Facebook page:

“As I try to go to sleep tonight…with visions of water all around the lighthouse … coming in from all directions … I’m thinking about a verse to a song I wrote…

“Through great storms and high waves East Point Lighthouse held fast

Through years of neglect, this old lighthouse did last

But the beach has eroded and time’s left its mark

It’s time to help East Point before it all goes dark

It’s time to give back now, it’s time to restore

Time to help East Point shine like before”

Storm Quinn was not as devastating as Riley. But another bomb cyclone, Skylar, was ramping up to hit the bay. On Saturday, March 10, help arrived. An army of volunteers appeared with food, a tractor, and tools to prepare for Skylar. During that storm, the beach was further eroded, with predictions for the fourth storm, Toby, a week later. The community’s pleas for help by telephone, social media, news reports and word of mouth resulted in an outpouring of local and state rescue teams.

Neighboring U.S. Silica [a sand-mining company] donated 3,000-pound sandbags, which were lined up in a wall along the beachfront to deflect the storm’s pounding waves. County and state crews brought in heavy sand-tracking equipment to secure the sandbags and build higher dunes. Toby blew in with less force than the earlier storms. With the massive sandbags in place and the dune stabilized, life slowly has resumed a tentative normal routine while government agencies attempt to find solutions to the fragile bayside environment and unpredictable threats from Mother Nature.

On a bright raw day in early April, Nancy and her grandchildren, Ella, now ten, and Jacob, age seven, were carrying vintage books to the keeper’s house. Jacob took a break, sitting in the sun, to read a Coast Guard manual about life saving stations. Lantern, the East Point Light cat, curled up on the windowsill. Nancy says she’s thinking her third illustrated book will feature Lantern. “She was a young feral kitty,” said Nancy. “I was unable to coax her. She ran off and hid in the marshes. Construction crews working daily on the restoration tamed her. We named her Lantern for the orange spot on her forehead that looks like a light. She takes our visitors on tour, all the way to the top.” Her favorite activity is walking the ledge in the lantern room overlooking the bay, where, from dusk to dawn and on dark, stormy days, East Point Light shines its trusty red beacon every three seconds.