Can Historic Preservation Save Cape May… Again?

Photo courtesy of Ben Miller.

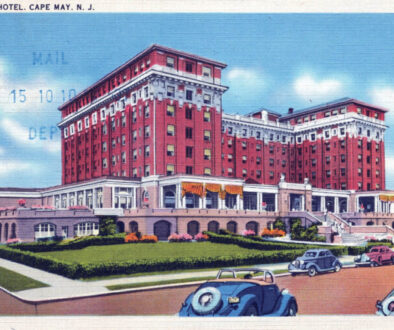

Photo courtesy of Ben Miller.

Seventy years ago, the summer crowd in Cape May settled in for another July and August season of fun. Beach time, swimming, parties, tennis, yachting, fishing, theater, and nightclubs filled up the days and nights of cottagers who made Cape May their home during the summer months. Many people owned summer properties, some passed down through generations, but even more summer residents did not own but rented the same house at a seasonal rate of $400 to $500 that might not even cover one night’s lodging in one of today’s resort properties. Cape May enjoyed a stable and loyal summer cottager following. Then, as now, people loved this small town where fishing, farming, and other occupations supported year-round residents whose incomes were further supplemented by summer residents. Skilled tradespeople took care of properties while others helped take care of children, cleaned, did laundry, and gardened. The many town businesspeople were extra busy during summer months supplying food, clothing, and other needed items. Summer visitors contributed to full-time residents’ incomes, but tourism was not yet the primary economic engine it would become.

As is always the case, nothing stays the same forever. The post-World War II years ushered in changes like car travel, suburbanization, and the demise of small-town central shopping districts. New innovations and conveniences became available for everyone. Washers and vacuum cleaners replaced maids and laundresses. People adopted new ways of living and working and, like other small towns across the country, Cape May began to change. The population decreased, children left town for more lucrative jobs in other places, fewer summer cottagers returned for the full season, once-profitable businesses failed, and the town’s old buildings became run-down. From these changes emerged the compelling and polarizing issue of the 1960s: should Cape May government and its citizens rally behind demolition, new construction, and modernizing the town or should the town’s future be built on a historic preservation agenda?

The town’s economy was already tipping to tourism as a primary revenue source. The argument at that time was that people (meaning tourists) did not want to stay in 100-year-old houses or old hotels. One group, called the ratables, held that tourists demanded clean rooms, their own baths, to park their cars right near where they were staying; they wanted the amenities available in other towns to be available in Cape May. If Cape May were to survive, the ratable group contended, the town needed to provide what the tourists wanted. The other group, called the preservationists, focused on the future, embracing the growing national historic preservation movement and interest in Victoriana while rallying around slogans such as “Our future is in our past.” The result of a more than ten-year struggle between the two groups was that while neither the ratables nor preservationists achieved a total win, the foundation for historic preservation in Cape May was established.

Did historic preservation save Cape May in the 1960s and 1970s? The answer pretty much depends on who is doing the reflecting, and while answers may be debated should anyone be interested, clearly the historic preservation activities taking place a half century ago provided the foundation on which today’s increasingly dominant heritage tourism economy is built. When out of town young people flocked to Cape May in the very early 1970’s, they were taken with the town’s architecture and the potential to create their own businesses in this picture-perfect town. They started stores, restaurants, and bed and breakfast inns. They joined the Chamber of Congress, Kiwanis, the local women’s club, the school boards and contributed hours of time to bolster this community in which they were now living. They were the town’s first hands-on preservationists, excited to restore the properties they were turning into businesses, often doing much of the work themselves and depending on each other to learn about Victorian construction techniques, furniture, and customs.

Tours and special weekends were created to bring tourists to Cape May to stay in the restored houses, shop in the town’s stores, and eat in local restaurants not just during the summer months but also during an ever-expanding shoulder season. These activities eventually were taken over by the then-named MidAtlantic Center for the Arts which not only successfully restored the Physick Estate but became the town’s primary organization for keeping tourists amused through tours, fairs, exhibits, music, special events and other activities which MAC has successfully delivered for the past 52 years.

At the same time, the out-of-town historians, so named by members of the ratable group, fostered recognition and preservation of the City’s historic resources. A loosely knit group of young Philadelphia historians, preservationists, architects, and photographers, they were successful in promoting Cape May’s 1970 designation as an historic district on both the State and National Registers of Historic Places and, later in 1976 as a National Landmark. Local townspeople, led by Dr. Irving Tenenbaum, a visionary for a future economy built on historic preservation tourism, pushed City government leaders to establish laws and requirements for preserving properties, obtain funding, and educate residents about the importance of preservation efforts to the town’s future economy.

The agenda was not to preserve the pretty Victorian houses but to orchestrate change to solidify the town’s future economic viability. By the end of the 1970s, the historic preservation agenda not only transformed Cape May into a successful tourist destination but distinguished it from other shore and beach resorts. Year after year, tourism thrived as people returned to their favorite Cape May haunts, bringing next generations along with them to this predominantly family resort.

A recent May 2022 article in the Philadelphia Inquirer offered a headline: “Change is Coming as Bed and Breakfasts Continue to Disappear and Longtime Beachfront Hotel Owners are Retiring and Selling Out.” One developer, Eustace Mita, is quoted as saying that “Vacationers want more from hotels than they did in the past. They’re used to high-end luxury. That is what they expect and want and there are less than a handful of full-service hotels in Cape May.” He goes on to say that Cape May is a “5-star resort with only one 5-star hotel—the 200-plus year-old Congress Hall”—pretty much the same argument of the 1960s ratable group who wanted to build those motels with parking and swimming pools because that is what the post-war culture wanted. Just think what Cape May would look like today if the ratable group had been more successful in creating change by destroying all the Victorian properties.

In this same article, Curtis Bashaw, owner of Cape Resorts, is quoted with a different view. He suggests that “There are so many beautiful structures that are architectural gems. Instead of building new structures, Cape Resorts renovates, restores, and preserves existing properties.” Bashaw has not only successfully restored Congress Hall (and other properties) physically and economically, but Cape Resorts has followed in the footsteps of those young people who came to Cape May 50 years ago by creating restaurants, amusements, shopping, and even a farm so that Cape Resorts guests always have something to do. Where else can you bring your kids with you on vacation to safely run around the Congress Hall lawn while you sip your evening drink at the Veranda Bar?

Historic preservation is not just about what a person or company is or is not permitted to do to a structure or piece of land. It is not just about individual properties or buildings but about community opportunities to share our past with future generations in ways that respect the cultural preferences of the present. Bill Murtaugh, a noted historic preservationist, may have said it best 60 years ago when he told attendees at an April 1962 Cape May conference that “historic preservation and restoration are an evolutionary and not a revolutionary process and that it isn’t necessary to create, but important to capitalize on the assets already here”—advice that Curtis Bashaw and others have acted on successfully. To quote Bashaw again from the same Inquirer story, “Change happens no matter what, so we do our best to manage it in a positive way,” bringing up the question of who has responsibility for managing change? Or more importantly, what evolutionary changes are needed or desired? And who do they benefit?

Cape May’s economy is based on the thousands of tourists who visit for a week or two each year to spend time in this idyllic little town that increasingly resembles a real-life Disney experience. Local government leaders, businesspeople, and residents may not have the resources to orchestrate this experience as effectively as the Disney Corporation manages their multi-million-dollar properties, but mechanisms are available to acknowledge and support the historic preservation foundation of the town’s economic success. One mechanism exists in Cape May’s historic preservation ordinances, implemented by a locally appointed Historic Preservation Commission (HPC). State and federal designations are awarded based on exceptional historic significance while local designations define the process and the rules for what may be done with and to properties within locally defined boundaries. Years before federal and state designations were even created, the Cape May City Council recognized the importance of historic preservation and established the Architectural Advisory Committee to advise and make recommendations to the City Planning Board. The Committee’s initial organizational meeting on March 22, 1962, was described in the Star and Wave as having a goal of developing a library of drawings, photographs, and other materials for use by residents and contractors as they were rehabilitating properties. Many buildings had been damaged in the 1962 Ash Wednesday Nor’easter storm and the town needed information and helpful advice to move forward.

This Committee went through changes and in 1987 was restructured as the Historic Preservation Commission (HPC). In 2000, the Zoning code was amended with ordinances demonstrating the importance of preservation to the community by creating a “strong” HPC, meaning that HPC decisions must be followed by the construction official rather than just being advisory. These changes also allowed the HPC to acquire Certified Local Government (CLG) status and eligibility for grant funding for projects supporting local historic preservation. Funds were used for publishing the 2002 award-winning City of Cape May Historic Preservation Commission Design Standards. Based on the earlier 1977 Cape May Handbook design guidelines, the 2002 Standards have become a model for communities in New Jersey and across the country.

Today the Commission reviews applications for both historic properties and new construction within the City’s historic district, granting Certificates of Appropriateness to those that meet the requirements of the Design Standards. The Standards provide examples of styles and materials, illustrating appropriate use within the local historic district; Certificates of Appropriateness are granted based on individual property reviews. Individual reviews are not the sole purpose of the HPC. The Commission’s purpose also includes advancing public purposes such as preserving resources for the general welfare of the public, strengthening the City’s economic base by stimulating tourism, and fostering civic pride in the beauty and accomplishments of the City’s past.

Historic preservation efforts across the country have weathered, and continue to survive, innumerable threats; Cape May is no exception. Think building demolitions, floods, new construction design, development, politics, popularity, or apathy, just to name a few. One given about history is that it repeats itself. The parallels between the 1960s/1970s “Cape May revival” and today’s development pressures are uncanny. Are preservationists once again strong enough to save Cape May from unmitigated change or will developers emerge to win today’s battles? Along with government officials, the City’s HPC is an overseer of historic resources but is insufficient as a sole protector of our heritage tourism industry. Many people want Cape May to hold onto its small-town characteristics and remain as a viable year around community while others are capitalizing on the town’s available economic potential and business opportunities. What Cape May will look like 50 years from now, in 2072, depends on today’s influencers in government, business, resident, and even tourist communities. If these and other groups step up and together intentionally guide changes while retaining the historic fabric of this real-life community, tourists will experience the Cape May they love and that returns them year after year. ■