A Walking Architectural Primer, Part Two

In our Spring issue, we featured architecturally significant buildings that were (and in some cases, still are) private homes. In this second walk, we focus on public buildings—gathering places for business, religion, theater and hospitality.

Among the many charms of Cape May is its distinctive quality as a walk-about town. Tree-lined streets, bordered by beautiful gardens, set the stage for Cape May’s colorful assemblage of carefully restored and preserved architecture. This collection of wooden structures, with abundant decorative detail, is considered one of the most diverse, architecturally significant in the nation, second only to San Francisco.

The core of the Historic District is within the same 35 acres that were destroyed in the Great Fire of 1878. The streets harken back to that era; they are narrow, designed for pedestrians and horse-drawn wagons and carriages. The Colonial and Victorian structures, built within a few feet of the streets, have defied the automobile age, and thus have protected the timeless atmosphere, the spell of the place, reaching back many generations.

The first street here is said to have been Jackson—originally a path Native Americans trekked in summer from upland woods and meadows to the beach to spear fish and gather mollusks. One of the first sites settled was the high ground on Beach Avenue between Congress and Perry Streets. There, in 1699, Thomas Hand, a first generation whaler from Long Island, purchased land for a large plantation—a place to graze cows and harvest hay. The epicenter of his acreage is where Congress Hall now stands.

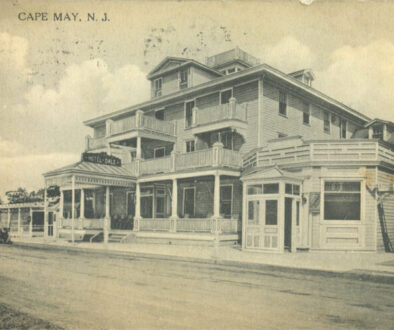

Congress Hall

200 Congress Place, Second Empire Style

Let’s begin at Congress Hall, in existence for more than 200 years, and described as the “oldest seaside hotel in the nation.” It was built in L-style to provide the maximum number of rooms with ocean views. The mansard roof, allowing for a fourth story of rooms, reflects Second Empire style, popular in France when Napoleon rebuilt Paris. Three-story verandas supported by 55 square wooden columns, decorated with brackets, tall windows and doors on the first level, give the hotel a southern plantation feel. This third version of the hotel was built in 1879 after the Great Fire of 1878 destroyed the property. Plans were drawn by architect J.F. Meyer for a “fireproof” structure in brick. A year later, architect Stephen Decatur Button designed a 100-foot addition and music pavilion. The red brick eventually was painted the signature yellow we see today. The multi-storied colonnade screening the bulk of the building also was used on other Cape May Hotels, including the Stockton, Lafayette and Chalfonte. President Benjamin Harrison established the Summer White House here in 1891. Presidents Franklin Pierce, James Buchanan and Ulysses Grant stayed at Congress Hall.

In this century, Congress Hall was completely renovated in a multi-million dollar project by Curtis Bashaw’s Cape Resorts, reopening in 2002.

The Carroll Villa

19 Jackson Street, American Bracketed Villa

At Perry Street and Beach Avenue, make a left on Beach to Jackson and another left to the Hildreth House, the Carroll Villa and Mad Batter Restaurant at 19 Jackson Street. It was commissioned by George Hildreth who called his new rooming house Carroll Villa in honor of Maryland’s Charles Carroll, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. It was built by local contractor Charles Shaw, and is one of several American Bracketed Villa styles seen in Cape May with flat roof, large cupola, center bay, and porch with pillars.

The Ebbitt House

25 Jackson Street, Circa 1879. Victorian flair later added

Adjacent to the Carroll Villa, the Virginia Hotel at 25 Jackson Street originally was called The Ebbitt House, after first owners, Alfred and Ellen Ebbitt. The name was changed to The Virginia in the 1890s when it was popular with southern visitors. It was built in 1879, a simple box of a building with flat roof, and two-story wrap-around porches with plain pillars and railings. Later, a Victorian flair was added with gingerbread arches, five on each of the two-story porches, plus lacey wood balustrades. The property was abandoned in the 1980s, but restored and reopened as a luxury boutique hotel by Curtis Bashaw and family in 1989.

Cape Island Presbyterian Church

405 Lafayette Street, Georgian vernacular with Moorish-style belfry

Now take a bit of a hike north on Jackson to the intersection of Lafayette and turn right several steps to the Robert Shackleton Playhouse on the left at 405 Lafayette. This 1853 former Cape Island Presbyterian Church also was once home to Methodists, then Episcopalians. It became the Cape May Stage theater in 1994 and has been carefully restored. The design and construction are credited to local builder Peter Hand. It is eclectic, called Georgian-vernacular, featuring a 20-foot tall onion-shaped Moorish style belfry. Moorish elements in design were popular in the mid-1800s.

Our Lady Star of the Sea Roman Catholic Church

Ocean and Washington Streets, Medieval Norman design with Romanesque arches

Walk east to Ocean Street and make a right to the Washington Street Mall. On the corner to the right is Our Lady Star of the Sea Roman Catholic Church. The cornerstone was laid in 1911, but the church was not completed until 1918 at the cost of $80,795. It was designed by George I. Lovatt, architect of many Philadelphia churches, and built by William McShane. It is Medieval Norman design with Romanesque arches. The exterior is grey granite with buff Indiana limestone trimming. The bell tower juts 80 feet high. The multiple-arched interior and altar showcase are Carrera marble. There are 40 stained glass windows produced especially for the church in 1913 by the prestigious Mayer and Company of Munich and New York. One hundred years later, in 2013, the church restored the windows as part of a $1.2 million renovation project.

New Jersey Trust and Safe Deposit Company

Ocean and Washington Street, Renaissance Revival style

Across the mall is the historic and architecturally significant former New Jersey Trust and Safe Deposit Company (now Winterwood Gifts & Christmas Shoppe). It was built in 1895 in Renaissance Revival style which takes cues from 16th- and 17th-century Italian palaces. The design, formal and symmetrical with limited ornamentation, lends itself to commercial buildings. The façade is broken by multiple large windows with minimal trim. The original design featured one large banking room with a sizable vault, offices, and a balcony. The vault, window grills, and iron gates were removed when the building served for a time as Cape May City Hall. Thomas Stevens of Camden was the architect.

First Presbyterian Church of Cape May

Decatur and Hughes Street, Gothic Revival style

Head toward the beach on Ocean Street, and at Hughes Street, make a right toward Decatur Street. On the corner is the imposing 1898 First Presbyterian Church of Cape May. The Gothic Revival style was the work of architect Isaac Purcell who studied with Samuel Sloan, the nationally famous architect of Philadelphia who designed the George Allen House on Washington Street, which we will visit later. The large 17’ x 17’ Gothic stained glass windows were produced by German-born Wilheim Reith whose studio was in Philadelphia. The congregation joined in a windows restoration project in 2007 at a cost of $206,000. Originally the church cost $21,500.

Ware’s Drug store

Ocean and Columbia Avenue, Designed by Charles Shaw in 1876

Return to the intersection of Ocean and Columbia, cross the street, and on the corner is the House of Royals, built and designed in 1876 by prolific Cape May contractor Charles Shaw. It is one of four buildings that make up The Queen Victoria bed and breakfast complex. This building was constructed as a gentleman’s gambling club. The second floor interior features 11-foot ceilings and nine-foot doors, with a large common room, and several smaller private gambler parlors. The deep mansard roof provides for a third floor and large capped windows. For years the building was Dr. Ware’s Drugstore.

The Colonial Hotel

Ocean and Beach Avenue, Second Empire lines featuring mansard roof

Head toward the beach on Ocean Street, and at the intersection with Beach Avenue is the large rambling four-story Colonial Hotel (now the Inn of Cape May). It is designed along Second Empire lines featuring a mansard roof with towers on the corners, and first- and second-story porches. It was designed and built in 1894–95 by West Cape May contractors William and C.S. Church. The south wing was added in 1905. The Colonial was unique in its era for providing year-round heat and an elevator, a 1900 vintage Otis, which is still in use.

The New Stockton Villa

727 Beach Avenue, Shingle style

Make a left on Beach Avenue to Howard Street, and at the intersection is the New Stockton Villa (now the Hotel Macomber), built in 1918. It is distinguished for being the last of the Historic Landmark structures to be built in Cape May. It is a good example of Shingle style with unpainted exterior wooden shingles and strong simple lines. Shingle style became popular for summer residences in Cape May and at other seashore resorts into the 1920s and ’30s. Its unadorned plain style blends well with sea, sky, and sand.

Chalfonte Hotel

Howard and Sewell Avenue, American Bracketed Villa

Head up Howard Street to the corner of Howard and Sewell Avenue and here is the Chalfonte Hotel, the most ornate hostelry in Cape May. It was built in 1876 by Civil War hero Henry Sawyer. The three-story building with cupola is considered American Bracketed Villa, a stylistic combination of elements from Italian Villa and Renaissance Revival architecture. Note the profuse cutout woodwork in balustrades and within scalloped arches on the long verandas supported by pillars. This artful construction creates a two-story, wrap-around colonnade which gives the building its lacey, wedding cake appearance. It is believed to be designed by local contractor Charles Shaw. It was built as a rooming house with heat, plus stables. A year later, the building was doubled in size and the cupola added. In 1879, Sawyer commissioned local builder D.D. Moore and Son to add the 100-foot wing on the Sewell Avenue side to accommodate a dining room and more guest rooms. This wing was further extended in 1888 and 1889. The Chalfonte was beyond the 1878 fire perimeter, and is thus the oldest continuously operating hotel in Cape May.

Jackson’s Clubhouse

635 Columbia Avenue, Italianate architecture

At Howard and Columbia, take a left turn to 635 Columbia and Jackson’s Clubhouse (now the Mainstay Inn Bed and Breakfast). This grand building, classic Italianate architecture, opened in 1872. It was designed specifically as a gentleman’s clubhouse. The cupola and tall, wrap-around bracketed porches, supported by a variety of columns, provide a southern antebellum image. The intent was to attract southern gentlemen who favored Cape May as a summer resort. The building was named after Charles Jackson who joined with fellow Philadelphian Robert Lear to conceive the clubhouse. They contracted Stephen Decatur Button to draw the design, which has a spacious mansion interior with many original furnishings. Local builders Hand and Ware managed the construction.

Church of the Advent

Franklin and Washington Street, Carpenter Gothic

At the end of Hughes Street, which runs behind the Mainstay, make a left on Franklin Street to Washington Street. On the left is Church of the Advent. It is Carpenter Gothic, and considered a classic example of this style with its board and batten siding, steep hip roofs, lancet windows in stained glass, chimney pot, and bargeboard. It was designed by Philadelphia architect Henry Sims, and Richard Soder was the builder, with construction beginning in 1867. The interior design of a Greek cross plan has been complimented by architectural surveyors for its “outstanding acoustics and light and airiness for a small church.”

George Allen House

720 Washington Street, Classic Italianate elements

At the intersection, stroll east on Washington to the George Allen House (now the Southern Mansion) on the right at number 720. This structure has been described as “One of New Jersey’s most impressive 19th-century seaside houses.” It was built in 1863–64 during the Civil War. It is another of Cape May’s architectural gems built during that war by a Philadelphian whose business fortunes expanded during the conflict. Allen owned several department stores. He engaged nationally famous Philadelphia architect Samuel Sloan, who specialized in Italianate villas, to design this large mansion, surrounded by extensive gardens. It has classic Italianate elements—high wrap-around porches, flat roof, wide eaves, imposing brackets—and was built using a sketch in one of Sloan’s pattern books. Sloan was a popular author credited with a lasting influence on American architecture.

Emlen Physick House & Carriage House

1048 Washington Street, Stick style. Features upside-down chimneys, signature of architect Frank Furness

It’s a hike down Washington Street—but worth it—to the Emlen Physick House, home to the Mid-Atlantic Center for the Arts and Humanities, at 1048 Washington Street. This house is a classic example of Stick style. Philadelphia architect Frank Furness is credited with designing this country house in 1878 for Dr. Emlen Physick Jr., originally on several acres with beautiful gardens. The large upside-down chimneys are a Furness signature. He also designed the interior with handsome stylized woodwork.

The façade has tall proportions with an irregular silhouette and structural overlays of building materials to emphasize the skeleton of the building, all elements of Stick style. Other characteristics are projecting bays, hooded jerkin-head dormers, and a large wrap-around veranda. The house was constructed by popular Cape May builder Charles Shaw.

The property fell into disrepair and was scheduled for demolition for a housing project in the 1970s. It was saved by preservationists who joined the efforts to make Cape May a National Historic Landmark in 1976.

The Physick Estate Carriage House, home of the Carroll Gallery, is also architecturally significant. It was built in 1876 prior to the main house. Its design was taken from drawings of A.M. Sidney, son of James C. Sidney of Philadelphia, the landscape designer of Cape May Point who also laid out plans for Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park.

This concludes our walking tour of Cape May—thank you for tagging along. Now go forth, enjoy, and appreciate your newfound knowledge of some of your favorite Cape May places.