The Rescue of a Slave and a Soldier

On a September morning in 1838, a young, enslaved man anxiously waited to board a train in Baltimore for Philadelphia. He was dressed as a mariner and had identification papers that he borrowed from a free Black sailor. He did not match the physical description on the government-issued certificate, but hoped no one would notice. This was Fred Bailey’s second effort to free himself, and he knew it would be his last opportunity. “I felt assured that, if I failed in this attempt, my case would be a hopeless one – it would seal my fate as a slave forever,” he later wrote.

Bailey’s journey to freedom was perilous – “The railroad from Baltimore to Philadelphia was under regulations so stringent that even free colored travelers were almost excluded. They must have free papers; they must be measured and carefully examined before they were allowed to enter the cars; they only went in the daytime, even when so examined. The steamboats were under regulations equally stringent,” he wrote. Fearing greater scrutiny by the ticket agent at the station, Bailey jumped on the train at the last minute and purchased a ticket from the conductor.

(GenealogyBank.com)

Some passengers on the train knew Bailey, and he feared he would be recognized and turned in. The almost four-hour ride to Wilmington, Delaware only made matters worse. “Minutes were hours, and hours were days during this part of my flight,” Bailey wrote. “The last point of imminent danger, and the one I dreaded most, was Wilmington. Here we left the train and took the steamboat for Philadelphia. In making the change here I again apprehended arrest, but no one disturbed me, and I was soon on the broad and beautiful Delaware, speeding away to the Quaker City.”

Hours after arriving in the free city of Philadelphia, Bailey boarded a train for New York. He soon changed his name to Frederick Douglass and became one of the most influential African Americans in history. He gave speeches, published newspapers, advised presidents, and wrote three autobiographies, beginning with Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845). Douglass dedicated his life to securing freedom and equality for everyone, and it helped change America.

Federal and state laws imposed harsh penalties on anyone who aided in the escape of a fugitive slave, but some vessels had a captain and crew who followed the philosophy: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” Crew members were often free Black men and women, working as deckhands, chambermaids, stewards, cooks, waiters, and firemen. The long hours and difficult conditions helped forge bonds between captains and their interracial crews. Fortunately, the steamboat that brought Douglass to freedom, named the Telegraph, was one of those vessels.

The Telegraph had side-mounted paddle wheels and measured 175 feet long, almost 20 feet longer than the Cape May Lighthouse is tall. When it was launched in 1836, the Wilmington Journal wrote: “She is probably the most beautiful boat on the river, and the fastest sailer. Her cabin is a splendid apartment, large, commodious, and beautifully ornamented.” It was built in a Philadelphia shipyard for Wilmon Whilldin, one of the earliest and most successful steamboat captains on the Delaware River.

Whilldin was born in Cape May in 1773. After being drawn to the area by the whaling industry, his Mayflower ancestors were among the first colonists to settle here in the late 1600s. They quickly became influential members of the community, and like other landowners in the county at the time, they were slaveholders. When Whilldin’s great-grandfather, Joseph Whilldin Jr., died in 1748, an inventory of his estate included “farm stock and 3 negroes.”

Wilmon left home at the age of 14 to work as an apprentice on a pilot boat in Philadelphia. He became a pilot at age 24, and by age 30 he was captain of a packet boat that formed a vital transportation link between Philadelphia and Baltimore. In 1812, at a time when there were few steamboats in the country, Whilldin took command of the steamboat Delaware, a modest boat steered with a tiller. John Quincy Adams was a frequent passenger, both before and during his presidency.

The Delaware became the first steamboat to offer regularly scheduled service between Philadelphia and Cape May, providing one leg of the voyage in 1816 and making the entire one-way trip in a single day by 1821. Whilldin later partnered with Cornelius Vanderbilt to transport passengers between Philadelphia and New York City, via Bordentown and New Brunswick, using steamboats and stagecoaches.

In 1838, Whilldin was under contract with the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad to ferry its passengers between Philadelphia and Wilmington while the newly formed railroad was still being built. He put his newest steamboat, the Telegraph, on the route, under the command of his son Wilmon, Jr. Born into a prosperous family in 1803, Wilmon Jr. received a medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania and practiced medicine for a few years before following in his father’s footsteps. In 1833, Wilmon Jr. brought President Andrew Jackson to Philadelphia on the steamboat Ohio. In 1837, he brought John Quincy Adams to Wilmington aboard the Telegraph.

Ten months after transporting Frederick Douglass to freedom, the Telegraph began making regular trips between Philadelphia and Cape May for the season.

Whilldin soon had other boats on the river, and during a time of prejudice and racial violence in Philadelphia, he began offering a discount to disadvantaged African Americans. In 1843, delegates attending the Mid-Atlantic Regional Temperance Convention of Colored Citizens, held in Salem, New Jersey, declared in their minutes: “On motion – a vote of thanks was tendered to Capt. Whilldin, of the Steamboat SUN, for his liberality in not charging full price for the passage of delegates to, and from the Convention.” Whilldin also took part in the Underground Railroad.

In his 1883 book, History of the Underground Railroad in Chester and the Neighboring Counties of Pennsylvania, Quaker physician Robert C. Smedley wrote: “At one time Friend Evans kept twenty-six at his place for two weeks, as he heard the hunters were assiduously watching for them in Philadelphia. When danger was past, he took them to James Lewis, there they remained until next night, when Dannaker, with two assistants, took them by different routes to Arch Street wharf, Philadelphia, arriving there at midnight. He put them on board Captain Whildon’s boat, which plied between Philadelphia, Trenton, and Bordentown. The captain kept a stateroom in which he carried fugitives whenever they could be put in there without exciting suspicion.”

Aiding enslaved people seeking freedom was dangerous work. In 1847, Samuel Burris, a free Black conductor on the Underground Railroad, attempted to help Maria Matthews escape to Philadelphia. They were apprehended before they could get onboard Whilldin’s steamboat near Smyrna, Delaware. Matthews was returned to slavery, and Burris was soon convicted in a state court of “enticing away slaves.” He was fined $500 and ordered to spend 10 more months in jail, after which he was to be sold at auction into slavery for 14 years. Unknown to the authorities, the winning bid came from an abolitionist posing as a slave trader. He was sent by the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society to purchase Burris and bring him back to his wife and children in Philadelphia.

When Wilmon Sr. died in 1852, a late-season storm blanketed Philadelphia with several inches of snow. That did not stop Whilldin’s friends from showing their respects. The Baltimore Sun reported “a long array of carriages and a large concourse of persons on foot attended the funeral.” The Philadelphia Public Ledger noted, “Among the persons attending the funeral were quite a number of colored men and women, who had been employed by the deceased upon the various steamboats he had commanded and owned.” The Daily National Intelligencer in Washington, D.C. eulogized Whilldin as “the friend of the needy and deserving; the foe of all monopolies.”

Among those who attended the funeral were people like David Wilson, a Black confectioner who started out as a mariner and became a deckhand for Whilldin in the 1830s. Wilson was likely among the crew members who helped transport Frederick Douglass to freedom. He rose to the position of engineer, before opening a cake, candy, and ice cream store with his wife in Chester, Pennsylvania. Located 15 miles south of Philadelphia on the Delaware River, Chester was a regular stop for Whildin’s steamboats and the Underground Railroad.

In 1845, Wilson and Stephen Smith, a wealthy Black lumber merchant, helped establish the Asbury AME Church in Chester. In that same year, Smith was a founder of the Allen AME Church in Cape May and prepared to build a summer house on Lafayette Street, which still exists today. Smith was born enslaved but purchased his freedom at the age of 21 and became a prominent anti-slavery and civil rights activist. According to Smedley, it was the attempted recapture of Smith’s mother in 1804 that gave rise to the Underground Railroad in Pennsylvania. [See “Stephen Smith, Cape May’s Underground Railroad Leader,” by Barbara Dreyfuss, Cape May Magazine, Fall 2015.]

Wilmon Jr. took over his father’s business. His steamboats continued to bring passengers to Cape May and provide a path to freedom on the Underground Railroad. Thomas Garrett, a prominent Quaker abolitionist who worked closely with Burris and Harriet Tubman, helped over 2,500 people escape slavery by any means available, including steamboats. In 1848, Garrett was convicted in a federal court of aiding in the escape of fugitive slaves and fined $5,400, which left him penniless but no less determined to help others.

In an 1856 letter to the chairman of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee, a secret group of Black and white abolitionists dedicated to helping enslaved people find freedom, Garrett wrote: “Respected Friend: – WILLIAM STILL: – Thine of yesterday, came to hand this morning, advising me to forward those four men to thee, which I propose to send from here in the steam boat, at two o’clock, P.M. today to thy care.” Every day at 7:30am and 2pm, Whilldin’s steamboats departed from Wilmington, Garrett’s home, bound for Philadelphia.

When Fort Sumter came under attack in April 1861—the first shots of the Civil War—Whilldin declared that if the government would consent to it, he would provision his steamboat and go to their aid. Whilldin’s steamboats, which brought passengers to Cape May in the summer of 1861, were soon chartered by the government to transport troops and supplies. He supported the effort to raise volunteer troops, including regiments at Camp William Penn, the largest training facility for Black soldiers during the war, located outside of Philadelphia.

Whilldin soon played a pivotal role in saving the life of Cape May’s Civil War hero, Captain Henry Sawyer of the First New Jersey Cavalry. In June 1863, Sawyer was nearly mortally wounded and left for dead at the Battle of Brandy Station in Virginia. Over 20,000 troops fought that day in what became the largest cavalry battle on American soil. Sawyer was carried off by the Confederates and soon taken to Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia. The three-story building on the James River was notorious for its poor treatment of Union officers and soldiers.

One month later, the imprisoned captains at Libby Prison were informed that two of them would be selected for execution in retaliation for the deaths of two Confederate officers who were convicted of spying. The first name drawn was Henry Sawyer, followed by John Flinn of the 51st Indiana Infantry. Details of their plight reached the newspapers and captured the attention of the nation.

Sawyer wrote to his wife in Cape May: “My Dear Wife: I am under the necessity of informing you that my prospects look dark. This morning all the Captains now prisoners at the Libby military prison drew lots for two to be executed. It fell to my lot . . . If I must die, a sacrifice to my country, with God’s will I must submit; only let me see you once more . . . Write to me as soon as you get this, and go to Captain Whilldin; he will advise you what to do.” Upon receiving the letter, Mrs. Sawyer rushed to inform her cousin, Captain Whilldin.

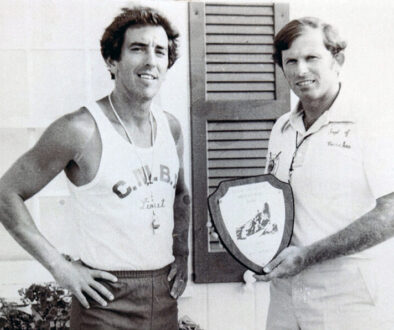

From left: Wilmon Whilldin Sr. Wilmon Whilldin Jr., ca. 1842, from the Semi-Centennial Memoir of the Harlan & Hollingsworth Company, 1836-1886 (HathiTrust.org)

Whilldin had influential friends in Philadelphia who urged him to speak with the president. He obtained a letter of introduction from Mayor Alexander Henry, who wrote: “To His Excellency, Abraham Lincoln, President U.S., Sir – I have the pleasure to introduce Capt. Wilmon Whilldin, one of the most estimable and loyal of the citizens of Philadelphia, who desires to interest you in behalf of his relative Capt. H. W. Sawyer, now at Richmond where he has been condemned by the rebels to die in retaliation for the execution of one of their own number. If any means can be adopted to avert such undeserved fate from a good soldier, I feel assured that Capt. Whilldin’s appeal will not be heard in vain.”

Whilldin and Mrs. Sawyer set out for Washington, D.C., and late that evening, they were granted an audience with the president. After reading Sawyer’s letter from Libby Prison, Lincoln told Mrs. Sawyer, “I do not know whether I can save your husband and Captain Flinn from the gallows, but I will do all in my power to do so.” It was a remarkable promise, considering that Lincoln was confronted with the realities of war each day.

Lincoln summoned his military advisers, who informed him that Brig. Gen. William H. F. “Rooney” Lee, the son of Robert E. Lee, commander of the Confederate Army, was being held in a Union prison. The next morning, Lincoln ordered the Confederate authorities to be informed that if Sawyer and Flinn, or “any other officers or men in the service of the United States not guilty of crimes punishable with death by the laws of war, shall be executed by the enemy,” Rooney and another Confederate officer selected would be immediately hung in retaliation.

Whilldin and Mrs. Sawyer proceeded to go to Libby Prison, carrying with them a pass from Secretary of War Edwin Stanton.But upon their arrival at City Point, Virginia, the Confederate authorities refused to allow them to proceed any further.

As days turned into weeks, Sawyer and Flinn were still alive but confined to a rat-infested dungeon, awaiting execution. Sawyer worried about the effect it was having on his wife and children. It also caused tremendous anguish for Robert E. Lee. Some newspapers at the time reported that Lee was opposed to executing Sawyer and Flinn and had threatened to resign from the rebel army if the Union executed his son in retaliation. Lee told his troops that the story was not true. He said that Sawyer and Flinn would be executed and vowed to never take another prisoner if anything happened to his son. Despite Lee’s assurances, Sawyer and Flinn were soon returned to the general prison population.

In March 1864, Sawyer, Flinn, and Rooney were finally released as part of a prisoner exchange. When Sawyer and Rooney met under the flag of truce, they shook hands and congratulated each other on their escape from death.

Two years later, Whilldin’s friends awoke to terrible news. The Philadelphia Daily Evening Bulletin reported: “Captain Wilmon Whilldin, an old and well-known steamboat captain of this city, died suddenly last evening. He was President of the New York and Philadelphia Steam Propeller Company, and was very prominently connected with our river navigation for many years . . . His character was irreproachable, his liberality and benevolence were of the noblest order, and we know of but few men whose death will be more universally mourned.”

Whilldin also served as President of the Board of Trustees of Old Pine Street Church in Philadelphia. Mary Brainerd, whose husband served as pastor of the church for 30 years, wrote that Captain Whilldin “was a man of ready sympathies, of most generous impulses, and prompt to aid, with heart and purse, every benevolent object which gained his approbation . . . and only a day or two before his death he went with Dr. Brainerd to examine the site for the new Mission School-house . . . and with characteristic enthusiasm assured Dr. Brainerd that he would see this enterprise through, if he had to build the house entirely himself.”

Whilldin enjoyed spending summers in Cape May. He would stay at the Ocean House on Perry Street, where he kept an apartment. In 1866, Whilldin’s daughter, Elizabeth, married the son of Joseph Leach, the former editor of the Cape MayOcean Wave newspaper. The following year, Henry Sawyer became the proprietor of the Ocean House.

In 1875, Sawyer began construction of a first-class boarding establishment on Howard Street in Cape May. He named it Sawyer’s Chalfonte, and it is celebrated today as Cape May’s oldest original hotel. After his wife died, Sawyer remarried and had a son named Henry. Years later, Henry Jr.’s son, Henry Sawyer III, earned a law degree from the University of Pennsylvania and became a prominent civil rights attorney. He went on to successfully argue two landmark cases involving the First Amendment before the U.S. Supreme Court.

Wilmon Whilldin Jr. has long been forgotten, but he and his father helped make Cape May a thriving seaside resort before the advent of railroads and automobiles. For 45 years, they welcomed all aboard their steamboats, befriending both presidents and slaves.