Good Save: The Resurrection of Congress Hall

Renovation photographs taken byJENNIFER BROWNSTONE KOPP and BERNIE HAASin 2002

Text by MARJORIE PRESTON

Over its 200-year-plus lifespan, Congress Hall has survived countless storms, both literal and figurative. It has lived at least nine lives and changed hands almost as often. It has survived fires, hurricanes, and the winds of war. It has been loved, neglected, and more than once, almost lost.

That the resort stands today is a testament to Cape Resorts managing partner Curtis Bashaw, his partners, and other champions who wouldn’t let the old girl die. On June 7, they will celebrate the 20th anniversary of a remarkable rescue—the $25 million, stem-to-stern overhaul that took almost a decade and restored the 19th-century hotel to its former glory, that should keep it in trim for another century or two.

Congress Hall’s turbulent history has been well documented, so here is the Cliff’s Notes version: First built in 1816 by Thomas Hughes, the rough-and-ready boardinghouse known as “The Big House” was ridiculed as “Tommy’s Folly” by critics who thought it too big to succeed.

They were wrong, but so was the choice to build a wooden structure in a city with a single fire truck. After the original building suffered a fire in 1818, Hughes rebuilt the Big House within a year. It lasted 60 years before it was reduced to rubble by the great fire of 1878. In its place, a new Congress Hall was built. Made of brick and painted a buttery yellow, it was distinguished by its L-shaped silhouette, 32-foot colonnade and mansard roof. In 1828, when Hughes was elected a New Jersey state representative, the Big House was renamed Congress Hall.

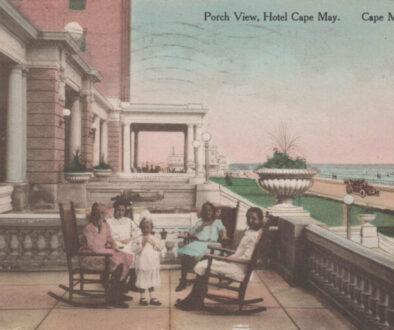

In its early heyday, the hotel was the watering hole of presidents including Franklin Pierce, Ulysses S. Grant, and Benjamin Harrison—so much so, it was dubbed the “presidents’ playground.” But over time, the fortunes of both Congress Hall and Cape May began a slow decline. Fast forward to the 1960s, and the former “grande dame” was a faded beauty—a little creaky and a lot worse for wear. By all appearances, her better days were behind her.

Enter the Preacher

That’s when the Reverend Carl Curtis McIntire, Jr. blew into town, on the heels of the catastrophic ’62 nor’easter. Perhaps one of the nation’s first televangelists, the firebrand preacher trumpeted his ultraconservative views on radio’s “Reformation Hour,” which briefly broadcast from a Navy minesweeper off the coast.

Through his enterprise, the Christian Beacon Press, McIntire began collecting island hotels like Monopoly tokens. They included the massive Hotel Cape May, a Beaux Arts beauty he promptly rechristened the Christian Admiral, and another oceanfront bastion, Congress Hall.

“He was an accidental preservationist,” says Bashaw, the grandson who is named for McIntire. “He didn’t come here to buy these old buildings and save them, but as a retreat, to have a gathering place for Christians from across the country. He wanted a place where they could be with each other and enjoy the seaside in a clean, safe environment.”

By that time, Cape May had fallen out of favor as a tourist destination, but McIntire did business “when traditional hotels had failed and kept failing,” says his grandson. By doing so, he likely saved them from the wrecking ball.

Bashaw remembers his first impression of Congress Hall, in the summer of 1967: “We were sitting on the beach as a family when my grandfather came down and said his company was going to buy Congress Hall. So, we got off the beach and walked through it, and it was this creepy kind of place with red-flocked wallpaper. I was like, ‘Oh gee.’”

But he soon fell in love with the old hotel, where he spent summers working and playing. In a 2019 interview with Forbes, Bashaw likened the experience to being Eloise at the Plaza: “Instead of having a beach house, we had a big beach hotel,” he said. “And it was a magical experience.”

As young as eight and nine years old, he says, “I moonlighted behind the desk, because I loved the enterprise aspect. Back then the old switchboard had those trunk lines that you connected rooms with. I would pester the desk clerk; her name was Kathy Boyer. And then, when I was old enough to work, I did. It’s been a lifelong relationship with this building.”

Along the way, he made note of the hotel’s imperfections, and told himself, “One day, I’m going to fix this building up.”

Throw Out the Lifeline

Former innkeeper Tom Carroll remembers the Cape May of the late 1960s, when he was first stationed at the Coast Guard Training Center. “The town was sad-looking, and poorly maintained,” Carroll says. “It certainly wasn’t attracting new people.”

When he and his wife, Sue, bought a 19th-century house on Columbia Street, friends shook their heads and said, “You’ll never unload it when you transfer.”

BEFORE AND AFTER:

Regrading and resurfacing, a new pool, and completely new landscaping were integral to the project.

Starting in the 1970s, a campaign was afoot to turn Cape May into Wildwood South: all neon-lit motels and kiddie parks, Ferris wheels and flash. Fortunately, by that time local sentiment had shifted toward appreciation of the city’s hundreds of Victorian-era homes and cottages. Preservation was the lifeline that would not only save Congress Hall but all of Cape May, and over time, turn it into one of the most desirable and popular vacation destinations in the world (per Travel & Leisure, “one of the best-preserved Victorian districts in America, with crape myrtles sprouting from sidewalks and American-flag bunting hanging from impeccable gingerbread porches”).

The Carroll home became the Mainstay, one of the city’s first and most beautiful bed-and-breakfast inns. And in 1976, following a campaign by historian Carolyn Pitts (called “Cape May’s avenging angel” by author Janice Wilson Stridick), the city was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

The transformation was on. Scores of private residences joined the ranks of B&Bs, those charming “painted ladies” with their candy colors and intricate woodwork. But the fate of Congress Hall was hardly assured.

McIntire’s ministries had fallen on hard times. His radio following had dwindled, along with donations from the faithful that paid the bills. The Christian Beacon Press went bankrupt, and its assets were lost. In the end, all that remained was a pile of debt, including some $500,000 in past-due city taxes.

It was time for Bashaw to make good on his youthful pledge. It was time to fix that building up.

Bashaw’s Folly?

In 1995, he negotiated financing that enabled him to buy back the Admiral Hotel and Congress Hall from the U.S. government, which had seized both properties. He also paid the past-due city taxes.

Then, in a decision that might have stumped King Solomon, he realized that to save one hotel, he had to sacrifice the other. Of the two properties, the Admiral was in worse shape by far, valued at just $85,000 on land worth $4 million. Bashaw opted to tear it down, sell the real estate and use the cash to help restore Congress Hall.

The Admiral was a beloved landmark, and news of its pending demise sparked outrage in some sectors, plus a series of legal and political challenges that would drag on for years. But there was no turning back. The Admiral was beyond reclamation, and in 1996, witnessed by grieving onlookers, it was demolished.

Meanwhile, time, tide, and the elements had taken a toll on Congress Hall. Yes, it had successfully dodged “undue development pressure,” according to research by Cape May architect Michael Calafati. But Congress Hall, wrote Calafati, was the victim of “self-inflicted” wounds that, without intervention, could have proven fatal. It was a money pit in the making, with defective plumbing, a sagging roof, and a legacy of ill-advised “repairs” that compromised its safety. Past owners had actually removed load-bearing elements, which had caused an interior collapse in the late 1970s. Cumulatively, problems caused by deferred and inept maintenance could cause “catastrophic failures,” Calafati wrote. Patchwork repairs would no longer do.

According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, when Bashaw undertook the massive renovation, friends and foes alike “thought he had a screw loose.” While he doesn’t disagree, Bashaw was undeterred, and may have been galvanized by the opposition.

“I understand that there are always critics, but it’s the person with the dust and the sweat on their face who gets the job done,” he says. “There were plenty of reasons not to do the project, but I was still full of youth—more or less—and passion. I was just a diehard optimist. I was going to finish this.”

Everything Old Is New Again

An army of workers descended on the site, for a job that would take the better part of a decade. In photos of the time, the disemboweled boiler room—now the Boiler Room restaurant and club—looks like it was hit by a meteor or bomb. Bashaw focused on the potential. “The building needed all new guts,” he says, “but it didn’t need a new structure.”

He recruited architect Finegold Alexander, whose heritage projects include the Ellis Island Museum of Immigration and Old City Hall in Boston. Interior design was the province of his sister, Colleen Bashaw.

While updating the property—they added private bathrooms for all accommodations (a first), plus a spa and a fitness center—the siblings worked to preserve as many original fixtures and fittings as possible, including the marble lobby floors, period chandeliers, porcelain shower bars, vintage 1920s bathtubs and a number of hand-blown glass windows.

Most of all, they sought to preserve the feeling of Congress Hall—genteel but relaxed and welcoming, and evocative of a bygone era that, for serenity alone, can be hard to recapture.

Colleen Bashaw’s goal, she says, was to “strip away all the preexisting notions I had about Congress Hall, and at the same time respect the history. I didn’t want to make it something fancy or over the top, because Congress Hall itself is very simple: an L-shaped building with rooms that are square and rectangular. I wanted it to be very nostalgic without being overly Victorian. This is not a building that’s stuck in time.”

She went for ease over opulence—for instance, using the same type of colorful striped rag rugs that had been part of the décor in the 1950s bedrooms. “I like design to be tongue-in-cheek—a little whimsical, very happy, like you’re in your grandmother’s beach house. But it should feel fresh and new at the same time.

“There wasn’t a huge budget, but a lot of heart went into the restoration of that building,” she says. And if the wooden floors continued to dip and creak in some places, that was okay too.

On June 7, 2002, following an exhaustive, every-nook-and-cranny renovation (final price tag: $25 million), all their hard work paid off. Congress Hall reopened with a ribbon-cutting and a weekend-long celebration, “a big open house for the whole town,” says Curtis Bashaw.

His only regret was that his grandfather wasn’t there. Carl McIntire had died at age 95, just a few months earlier. “He would have been proud,” says Bashaw. “He was proud.”

Thirty-five years had passed since Bashaw first set foot in the old hotel with its red-flocked wallpaper, and a quarter century since he began working there full-time. At one point during the reopening, he drifted away from the crowd, then observed the festivities from a distance. “It was a really cool private moment to just sort of understand all that it took to get there.”

Defending the Pink

Change is a constant, but as the saying goes, “it pinches sometimes.” In 2016, Colleen Bashaw redecorated the hotel’s venerable Brown Room, pulling up the familiar zebra-print carpet, installing a new parquet floor, recovering the chocolate-brown walls, and replacing the bar. Some of the bar’s patrons were apoplectic.

This spring, a similar controversy brewed when she repainted the hotel’s 3,500-square-foot ballroom. For 20 years it had been pale blue, like a Tiffany gift-box. Now the walls are a creamy shell pink, contrasting dramatically with the black-and-white pattern of the dance floor.

Once again, an uproar. “I’ve had so many people say, ‘The Tiffany blue is iconic. How can you change it?’” says Colleen. “When I did the blue years ago, it just felt right. But over time, with painting and repainting, it became very heavy. The pink is ethereal. It’s going to be so pretty.”

She thinks the pushback speaks to the affection people have for Congress Hall. “They feel like they’re part owners—it’s a generational thing. This is a summer house for a lot of different families. The thought of changing it is scary, but then when change happens and they’re in the space, they’re transported. After the Brown Room was finally done, I got a ton of apologies— ‘I’m so sorry. I was so harsh. It’s so beautiful.’”

Likewise, she hopes people will come to love the pink ballroom, which she calls “transcendent.”

Today, it would be no exaggeration to rank Congress Hall among the great historic hotels in the country: the Peabody in Memphis; the Algonquin in New York; the Grand Hotel on Mackinac Island, Michigan; Chicago’s Palmer House; the Hotel del Coronado in California.

“It’s a repository of tradition,” says Curtis Bashaw. “People ask me all the time, ‘Is it haunted?’ Well, yes, it is, in the best sense of the word. It’s spirit-filled with the memories and traditions of 204 years of vacationers, of employees and leaders and visiting dignitaries. It’s been an amazing journey, and so fun to see how people love it.”

For him, the saga of Congress Hall, with all its ups and downs, recalls the The Great Exotic Marigold Hotel. The 2011 film tells the story of a Jaipur hotel, teetering on the verge of extinction, and the harried manager who tries to save it.

“Oh, that silly, sad, fun, sweet movie,” Bashaw says. “That boy who was starting that hotel—he reminds me of me in those years.” ■

In the Mid-Summer 2022 Issue: Part II Pillars and Presidents